More than ever these days, with the world in ever increasing chaos, escaping into a good book seems to be a way to hold onto one’s sanity!

As a child, when I was feeling down or stayed home from school because I was sick, I often turned to my same favourite book and read it again. As an adult, however, I seldom reread books. I first read this month’s feature trilogy soon after the third book was published in 1995. The boxed set has been sitting on a shelf downstairs for almost three decades and lately it had been calling out to me. Although I remembered the main characters and knew that the story had impacted me the first time I read it, I couldn’t recall many of the details. It was definitely worth a second read.

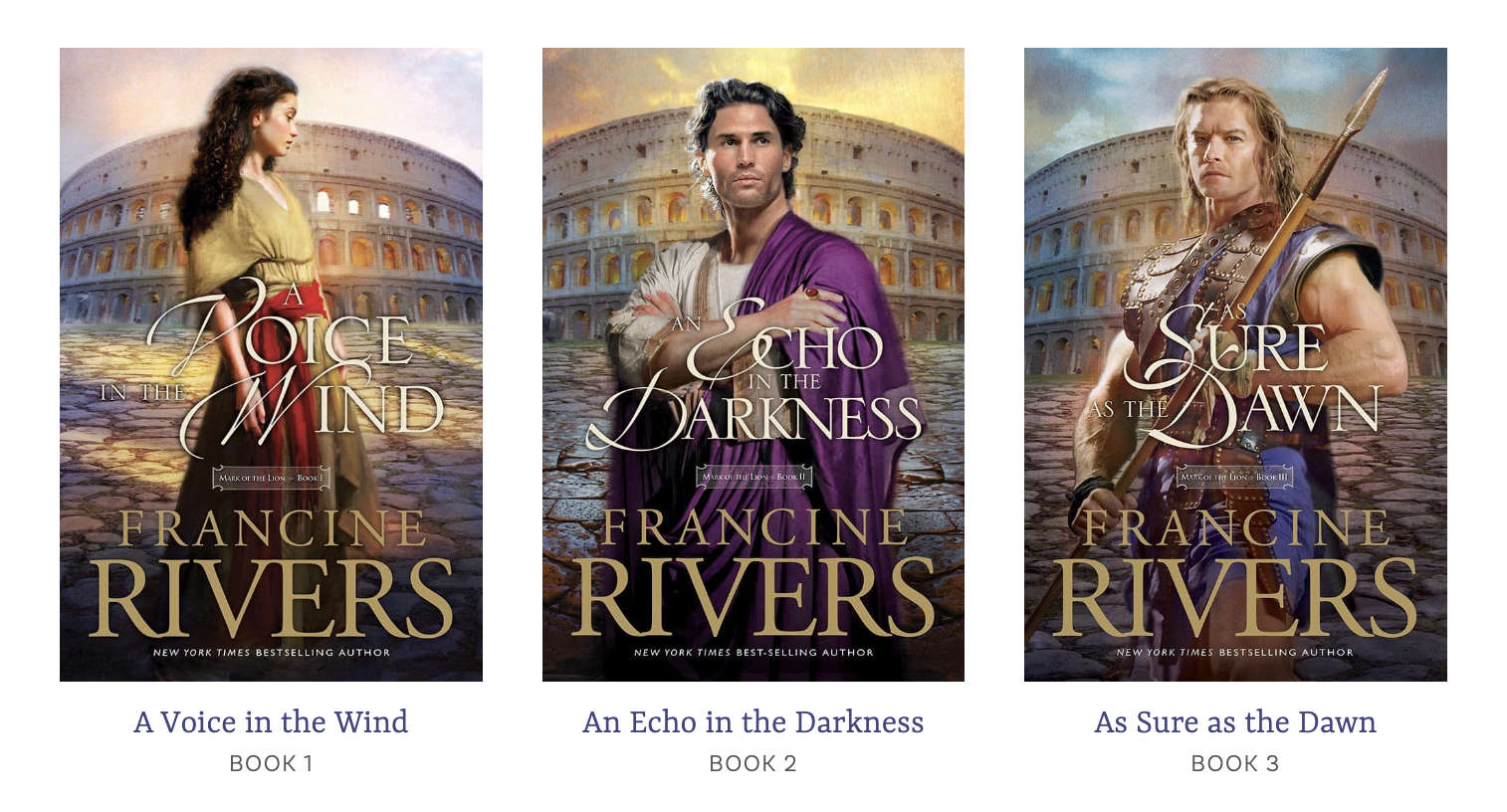

Mark of the Lion

Francine Rivers

I seldom read Christian novels because most of them are either futuristic stories based on the author’s interpretation of the Biblical book of Revelation or fluffy happy-ever-after romances. These three books definitely don’t fall into either of those categories. In fact, they are best suited to a mature audience that isn’t overly squeamish as there are some fairly graphic descriptions of violence and cruelty, as well as references to sexuality and sexually transmitted disease, discrimination, and other forms of injustice. For those who like romance, though, there’s also some of that!

Set mainly in 1st century Rome and Ephesus, this is a story of courage, faith, forgiveness, and redemption. The main characters include Hadassah, a young girl captured during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD and sold into slavery; the Valerians, a wealthy and aristocratic Roman family; and Atretes, a German warrior captured and trained as a gladiator. In addition, the author weaves in a whole host of other characters including several from the Bible, fictionalized of course.

Rivers does an outstanding job of vividly portraying the decadent culture of 1st century Rome and at times it seems all too familiar as many of the same issues still plague us today. One would have to wonder if contemporary Western culture is destined to fall in much the same way that corrupt Rome did, but I digress!

The core message of Christianity is woven throughout the series and clearly motivates some of the characters, but Rivers has managed to incorporate this without becoming preachy.

Even the second time through, I could hardly put these books down. In the words of one Goodreads reviewer, “These are can’t put down, aren’t going to feed the kids or the dog, not doing laundry kind of books!” Fortunately, my kids have all flown the nest and we don’t have a dog!

Buying a Piece of Paris is a charming memoir about the Australian author’s humorous and challenging quest to find and purchase an apartment in Paris. With only two weeks to locate and secure the apartment of her dreams, something exuding character and Parisian chic, Ellie embarks on what seems an almost impossible pursuit. Armed with only a cursory grasp of the language, she finds herself trying to navigate the bewildering French real estate market with its unique customs, quirky agents, and unexpected cultural hurdles. All in all, a very entertaining read and especially so since, although I’ve only spent five days in Paris, I could visualize many of the places that she mentioned and the kind of buildings she visited in her frantic and sometimes hilarious search for the perfect place to call home.

Buying a Piece of Paris is a charming memoir about the Australian author’s humorous and challenging quest to find and purchase an apartment in Paris. With only two weeks to locate and secure the apartment of her dreams, something exuding character and Parisian chic, Ellie embarks on what seems an almost impossible pursuit. Armed with only a cursory grasp of the language, she finds herself trying to navigate the bewildering French real estate market with its unique customs, quirky agents, and unexpected cultural hurdles. All in all, a very entertaining read and especially so since, although I’ve only spent five days in Paris, I could visualize many of the places that she mentioned and the kind of buildings she visited in her frantic and sometimes hilarious search for the perfect place to call home.

After moving with her husband to the tiny, bustling city of Macau, across the Pearl River delta from Hong Kong, Grace Miller finds herself a stranger in a very foreign land. Facing the devastating news of her infertility and a marriage in crisis, Grace resolves to do something bold, something that her impetuous mother might have done. Turning to her love of baking, she opens Lillian’s, a café specializing in coffee, tea, and delicate French macarons. In this story of love, friendship, and renewal, Lillian’s quickly becomes a sanctuary where women from different cultural backgrounds come together to support one another.

After moving with her husband to the tiny, bustling city of Macau, across the Pearl River delta from Hong Kong, Grace Miller finds herself a stranger in a very foreign land. Facing the devastating news of her infertility and a marriage in crisis, Grace resolves to do something bold, something that her impetuous mother might have done. Turning to her love of baking, she opens Lillian’s, a café specializing in coffee, tea, and delicate French macarons. In this story of love, friendship, and renewal, Lillian’s quickly becomes a sanctuary where women from different cultural backgrounds come together to support one another.

When Jennifer Connolly of

When Jennifer Connolly of

If I didn’t know that this novel was was a well-researched, but fictionalized retelling of a true story I would have thought it a bit far-fetched. A father giving his 16-year-old daughter control of three family plantations in South Carolina while he leaves the country to secure his political position on the Caribbean island of Antigua would be remarkable at any time, but this was 1738! At a time when the role of women was purely domestic, intelligent and headstrong Eliza Lucas was determined to find a cash crop to pull the plantations out of debt, pay for their upkeep, and support her family.

If I didn’t know that this novel was was a well-researched, but fictionalized retelling of a true story I would have thought it a bit far-fetched. A father giving his 16-year-old daughter control of three family plantations in South Carolina while he leaves the country to secure his political position on the Caribbean island of Antigua would be remarkable at any time, but this was 1738! At a time when the role of women was purely domestic, intelligent and headstrong Eliza Lucas was determined to find a cash crop to pull the plantations out of debt, pay for their upkeep, and support her family. This book is really three stories in one, each distinct, but all connected. Deborah Birch is a seasoned hospice nurse assigned to care for an embittered and lonely history professor whose career ended in academic scandal. As his life slowly ebbs away, the professor, an expert in the Pacific Theater of World War II, begrudgingly puts his trust in Deborah and begins to share with her an unpublished book that he wrote. As she reads to him from his story about a Japanese fighter pilot who dropped bombs on the coastline of Oregon, he challenges her to decide if it is true or not.

This book is really three stories in one, each distinct, but all connected. Deborah Birch is a seasoned hospice nurse assigned to care for an embittered and lonely history professor whose career ended in academic scandal. As his life slowly ebbs away, the professor, an expert in the Pacific Theater of World War II, begrudgingly puts his trust in Deborah and begins to share with her an unpublished book that he wrote. As she reads to him from his story about a Japanese fighter pilot who dropped bombs on the coastline of Oregon, he challenges her to decide if it is true or not. I’ve been avoiding books set during World War II lately. Over the past year or so I’d read so many of that popular genre that I was growing weary of them, but The Book Thief was different from most.

I’ve been avoiding books set during World War II lately. Over the past year or so I’d read so many of that popular genre that I was growing weary of them, but The Book Thief was different from most.

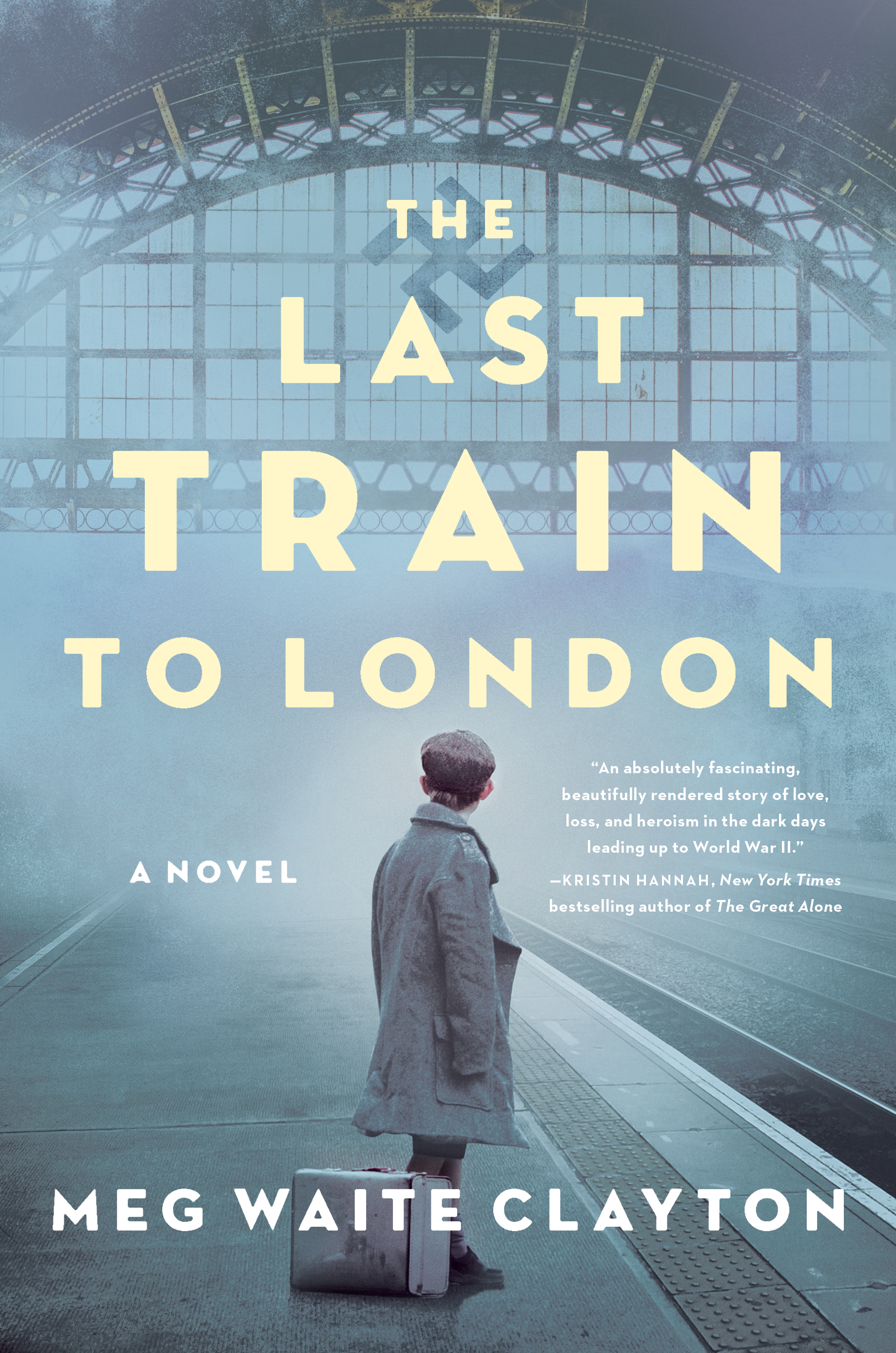

Until the end, when the two finally come together, this is really two completely different storylines connected only by a specific location.

Until the end, when the two finally come together, this is really two completely different storylines connected only by a specific location. Geertruida (Truus) Wijsmuller, a childless member of the Dutch resistance, risks her life smuggling Jewish children out of Nazi Germany to the nations that will take them. It is a mission that becomes even more dangerous after Hitler’s annexation of Austria when, across Europe, countries begin to close their borders to the growing number of refugees desperate to escape. After Britain passes a measure to take in at-risk child refugees from the German Reich, Tante Truus, as she is known by the children, dares to approach Adolf Eichmann, the man who would later help devise the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” and is granted permission to escort a trainload of 600 children (not 599 or 601, but exactly 600) out of the country. In a race against time, 600 children between the ages of 4 and 17 are registered, photographed, checked by medical doctors and put on board the train to begin a perilous journey to an uncertain future abroad. Thus begins the famous Kindertransport system that went on to transport thousands of children out of various parts of Europe during the Nazi occupation of the region in the late 1930s, immediately prior to the official start of World War II.

Geertruida (Truus) Wijsmuller, a childless member of the Dutch resistance, risks her life smuggling Jewish children out of Nazi Germany to the nations that will take them. It is a mission that becomes even more dangerous after Hitler’s annexation of Austria when, across Europe, countries begin to close their borders to the growing number of refugees desperate to escape. After Britain passes a measure to take in at-risk child refugees from the German Reich, Tante Truus, as she is known by the children, dares to approach Adolf Eichmann, the man who would later help devise the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” and is granted permission to escort a trainload of 600 children (not 599 or 601, but exactly 600) out of the country. In a race against time, 600 children between the ages of 4 and 17 are registered, photographed, checked by medical doctors and put on board the train to begin a perilous journey to an uncertain future abroad. Thus begins the famous Kindertransport system that went on to transport thousands of children out of various parts of Europe during the Nazi occupation of the region in the late 1930s, immediately prior to the official start of World War II.